Next to Use 3D Printing: Your Surgeon

Surgeons at a hospital in Japan recently faced a dilemma before transplanting a parent’s liver into a child: How exactly to trim the organ to fit the space in the child’s smaller cavity while preserving its functions.

Surgeons at a hospital in Japan recently faced a dilemma before transplanting a parent’s liver into a child: How exactly to trim the organ to fit the space in the child’s smaller cavity while preserving its functions.

So they took a knife to a three-dimensional replica of the donor’s liver built by a machine that resembles an office printer. The model helped the doctors figure out where to carve it, leading to a successful transplant last month.

Surgeons are finding industrial 3-D printers to be a lifesaver on the operating table. This technology, also known as additive manufacturing, has long produced prototypes of jewelry, electronics and car parts. But now these industrial printers are able to construct personalized copies of livers and kidneys, one ultrathin layer at a time.

The medical field in particular is expected to benefit greatly from 3-D printing. Scientists are working on ways to print embryonic stem cells and living human tissue with the aim to produce body parts that can be directly attached to or implanted in the body.

Printing out artificial body parts is likely many years away, but advanced 3-D printers are starting to make their mark at hospitals.

Two of the world’s largest industrial 3-D printer makers, U.S. companies Stratasys Ltd. SSYS +1.84% and 3D Systems Corp., DDD +2.87% offer machines that can replicate human organs.

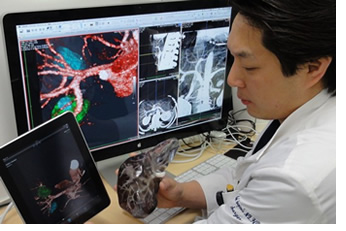

Using medical images such as CT scans, these printers can construct translucent models made with variations of acrylic resin, enabling surgeons to understand the internal structure of the livers and kidneys, such as the direction of blood vessels or the exact location of a tumor.

A more realistic-looking model, made partly of polyvinyl alcohol, assimilates the wetness and texture of a real human liver, making it more suitable to cut with a surgical knife.

It usually takes several hours to a half day to print a copy of a human organ depending on its size. The whole process, including the time to convert the original medical images to printable 3-D data, usually takes a few days.

“Today, most medical uses [of 3-D printers] are still experimental, but we are seeing more and more applications,” said David Reis, chief executive of Stratasys, based in Eden Prairie, Minn.

There are many hurdles, to be sure, before the technology can become widespread in operating rooms at hospitals world-wide. The kinds of advanced 3-D printers used to create organ models can cost between $250,000 to $500,000, making it difficult for smaller hospitals to install them.

As most doctors don’t know how to use those printers, hospitals need engineers to operate the printers and help convert images from computed tomography and other medical equipment to 3-D data that can be printed out.

Maki Sugimoto, a surgeon at Japan’s Kobe University Hospital who began using replicas of patients’ organs for navigation purposes in 2011, employs Japanese company Fasotec Co. to produce the 3-D models. Fasotec acts as an intermediary between the hospitals and printers.

Fasotec says it is still rare for surgeons to request 3-D replicas of internal organs—more typical are basic 3-D copies of bones.

At Hong Kong’s Dental Implant & Maxillofacial Centre, oral surgeons have been using 3-D printers for a few years to create not only a copy of the patient’s jaw to plan surgeries, but also a custom-made surgery template that can be placed inside the patient’s mouth during the operation so the doctor knows exactly where to insert implants.

Efforts to promote 3-D printing for surgical purposes come at a time when the technology is evolving faster, drawing renewed attention in the media and generating buzz among consumers world-wide.

While 3-D printing has existed for about 30 years, the rapid progress in technology in recent years, as well as more affordable price tags, has made the technology more attractive to industries and consumers.

In the U.S., some universities and corporate laboratories are conducting research on “bioprinting,” or artificial construction of body parts using living human tissue. Still in the experimental phase, researchers hope one day to produce personalized body parts on demand, despite many hurdles including ethical questions.

Mr. Sugimoto believes that longer-term, the technology could help younger, less experienced surgeons practice with accurate copies before surgery.

If doctors feel more confident about the surgeries they are about to perform, patients will feel more comfortable, Mr. Sugimoto said.

“The potential impact is no smaller than the shift from fixed-line phones to mobile phones,” he said.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!